4 Most Common Mistakes That Coaches Make When Evaluating Talent

Talent identification is one of the most critical and most misunderstood elements in coaching.

Regardless of the level that you are coaching, your ability to accurately evaluate talent will shape your reputation, program culture, credibility, and, oftentimes, even your success.

And yet, evaluating talent is one of the easiest places for even experienced coaches to go wrong.

Talent isn’t always obvious.

It’s rarely loud. And it's rarely enough on its own.

In this essay, we’ll explore the four most common mistakes coaches make when evaluating talent in youth sports.

These errors don't just lead to missed opportunities. They can derail a player’s development, break trust within your team, and create long-term limitations on what your program can become.

Let’s unpack each one, with practical examples, underlying psychology, and corrective strategies to help you sharpen your eye and raise your standard.

Mistake #1: Overvaluing Physical Maturity and Early Bloomers

One of the most common, and costly, errors in youth sport talent identification is mistaking early physical development for long-term potential.

Coaches often gravitate toward the biggest, fastest, or strongest players. They stand out. They dominate at younger age levels. They win sprints. They rack up stats.

But in many cases, they’re simply physically more advanced, not more talented.

Why it happens:

Cognitive bias: Our brains are wired to associate size and strength with dominance. A 14-year-old who looks 17 is assumed to be better.

Outcome focus: Coaches pressured to win now often lean on physically mature players to get immediate results.

Highlight bias: These players often produce more “standout” moments. Big plays that grab attention, but don’t always indicate deeper skill.

The long-term issue:

Early maturers often plateau earlier if they haven’t been forced to develop decision-making, technique, or resilience. Meanwhile, late developers get overlooked, despite having higher ceilings.

Real-World Example:

A coach selects a tall, dominant centre for a regional team, bypassing a smaller but more skilled forward.

Two years later, the taller player is no longer progressing, while the overlooked player, now physically caught up, earns a spot in a national program. The difference? One relied on early strength. The other built skills and grit.

Roger Federer was not the most physically dominant junior, but became arguably the best tennis player of all time through technical brilliance and intelligence.

Giannis Antetokounmpo was skinny and less physically developed compared to other NBA players, but he developed explosiveness and strength over time.

Steph Curry and Leo Messi are also examples of players who came into their own later rather than earlier.

What to do instead:

Look beyond current dominance. Ask: What will this player look like in 3 years?

Reward decision-making, technique, and adaptability, not just physical outcomes.

Talent isn’t about who looks ready now; it’s all about who has the tools to be excellent later.

Mistake #2: Confusing Confidence with Competence

It’s easy to be seduced by swagger.

Players who carry themselves with confidence. They maintain eye contact, communicate loudly, and have a sense of bravado often give off the impression that they know what they’re doing. Sometimes they do.

But sometimes, that confidence masks gaps in understanding, discipline, or consistency.

Why it happens:

First impressions: Players who appear assertive create the illusion of leadership and readiness.

Coach projection: Coaches often want players with “presence” and assume confidence equals ability.

Noise over substance: A loud voice or flashy play can distract from flaws in fundamentals.

The risk:

Confident-but-undisciplined players may fail to improve because their mindset is rooted in proving, not learning. Worse, they can disrupt team culture, resist coaching, and overestimate their role.

Real-World Example:

A guard at a showcase talks non-stop, takes deep threes, points at teammates, and celebrates every basket. Recruiters mark him as a “floor general.”

But in film review, it’s clear: he misses defensive rotations, turns the ball over under pressure, and doesn’t apply feedback. Meanwhile, a quieter player executes plays, communicates efficiently, and adapts mid-game, but is passed over for being “reserved.”

Dennis Rodman was loud, brash and extremely confident, which sometimes overshadowed his actual performance. Although eventually, he proved himself as an elite rebounder and defender, there were times when his personality raised questions about his level of competence and whether he was a good fit for the team.

What to do instead:

Separate style from substance. Ask: Does this player make others better?

Watch how they handle feedback and failure. Real competence shows in correction, not celebration.

Give quieter players a chance to lead in different formats. Confidence can grow, but character is harder to teach.

Evaluating competence means listening beyond the volume.

Mistake #3: Overemphasising Game Performance, Underemphasising Practice Habits

Some players are “gamers.” Others are “trainers.”

But the best players are both. Coaches often evaluate talent based almost exclusively on game performance, stats, impact plays, and body language under pressure.

But how a player trains is often a stronger predictor of long-term growth.

Why it happens:

Games are public. Everyone watches.

Games are measurable. Points, assists, win/loss. They are easily tracked.

Training is subtle. Effort, focus, repetition, attitude. These are harder to quantify, but more revealing.

The risk:

Selecting players who only “switch on” for games can create inconsistency, entitlement, and stagnation. Players who dominate a few big games but don’t train with intention often hit ceilings earlier.

An Example:

During a tryout, a forward plays exceptionally in scrimmages. He has high energy, great stats. But over several practices, he cuts corners in warmups, is resistant to film study, and mocks less skilled players. Another athlete, less dominant in games, brings intensity, asks questions, and improves visibly session to session.

The second player is more likely to end up outperforming the first after a couple of weeks.

What to do instead:

Weigh practice habits as heavily as game performance in selection decisions.

Track consistency in effort, focus, and improvement over time.

Ask: Would I want to coach this player every day? Not just on game day.

Practice is where long-term talent is forged, not just revealed.

Mistake #4: Ignoring Context and System Fit

One of the most overlooked aspects of evaluating talent is context: the fit between a player’s skillset and your team’s style, philosophy, or system.

A great player in the wrong environment often underperforms, not because they lack talent, but because they’re not being used in ways that align with their strengths.

Why it happens:

Over-reliance on raw ability: Coaches assume that talent will translate across systems.

Lack of system clarity: If coaches aren’t clear on their own style, they can’t spot the right fit.

Pressure to “collect talent”: Programs often focus on accumulating the most talent instead of assembling the right mix.

The risk:

Clashing styles: A possession-based soccer team signs a direct-play striker, who never touches the ball.

Frustrated development: A playmaking guard joins a team that already has two high-usage guards.

Damaged trust: Players feel mismatched, underused, or misled, hurting development and team dynamics.

Real-World Example:

A club team recruits an ultra-athletic wing known for iso scoring.

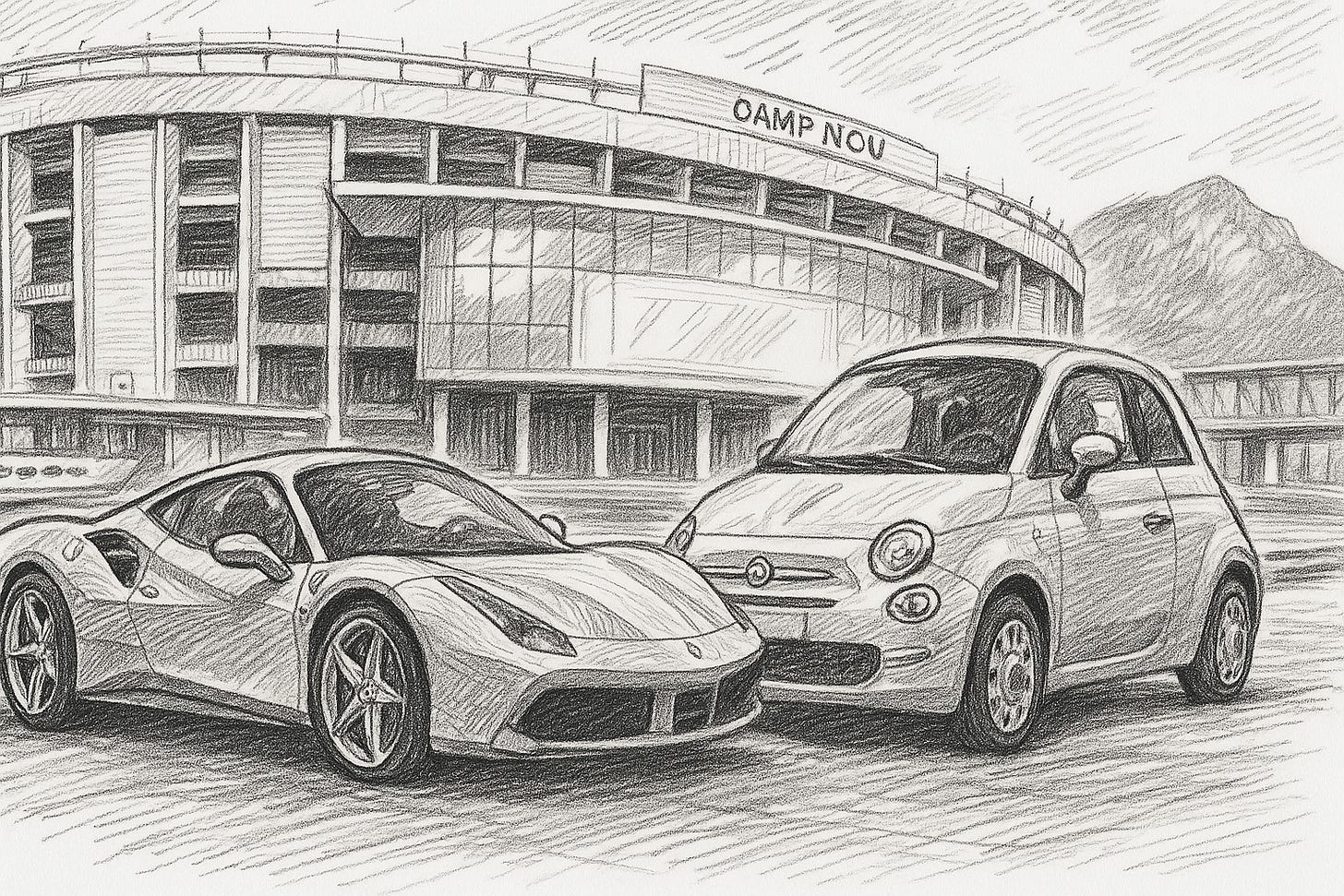

The team, however, plays a motion offense with ball-sharing principles. The player struggles, forces shots, and grows frustrated. Meanwhile, a less-hyped passer who reads the game well becomes the unexpected linchpin of the offense. This is exactly what happened in Barcelona with Zlatan Ibrahimovic and Lionel Messi.

Ibrahimovic struggled under Guardiola’s possession-based, highly tactical system. This resulted in a fallout between him and the Club. Eventually, he parted ways, frustrated, saying, “You can’t buy a Ferrari and drive it like a Fiat!”

Steve Nash excelled in the run-and-gun system of the Phoenix Suns, where he was able to optimise his strength as a pick-and-roll guard, playing alongside Stoudemire. But, before that, at Mavericks or later with the Lakers, he struggled because of the system fit.

What to do instead:

Know your system and style. Be crystal clear on how you play and what you need.

Evaluate players in context. Ask: Does this player solve a problem we actually have?

Build balance, not just firepower. The best teams have puzzle pieces that fit.

Fit amplifies talent. Misfit nullifies it.

Evaluation is a skill that needs to be refined relentlessly

Great coaching begins with great observation.

The ability to evaluate talent accurately, not just in terms of ability, but in terms of attitude, coachability, consistency, and contextual fit, is one of the most important tools a coach can develop.

Don’t confuse early maturity with long-term potential. Look beyond size and strength.

Don’t mistake confidence for competence. Look for substance beneath the style.

Don’t evaluate only in games. How they train is who they really are.

Don’t ignore fit. A great player in the wrong system will underperform.

For Youth and Part-Time Coaches:

Remember: your influence on a player's journey is massive. By sharpening your eye, asking better questions, and resisting easy assumptions, you’re not just selecting talent, you’re shaping futures.

Create multi-phase evaluation processes: not just one trial, but repeated exposure across different formats (games, drills, challenges, discussions).

Value character, learning mindset, and work habits as much as highlight moments.

Coaching is a long game. Talent evaluation is where that game begins.

Evaluate smarter. Coach better. What you reward is what you grow!